Since 2000 over 6,000 migrants have died trying to cross the US-Mexico border. State of Exception/Estado de Excepción, an exhibit at the Parsons School of Design, uses discarded and found objects including clothing, prayer cards, and backpacks to pay homage to those who have lost their lives as well as those who survived the dangerous journey across the border. The materials were collected as part of a research project (called “Undocumented Migration”) by University of Michigan anthropologist Jason De León. He views the “materials as fragments of a history, revealing death, trauma, and suffering on both sides of the border while bringing to light complexities of the migrant experience.”

The exhibit begins with a video installation called Debris Field, Sonoran Desert consisting of four different images projected over the floor. Walking over the images—featuring shots of a stretch of the desert covered in discarded backpacks, clothes, water bottles, and other everyday objects—is visually disorientating, giving the viewer a small sense of what migrants might feel walking over the treacherous terrain. The Sonoran Desert is one of the hottest and driest stretches of desert in North America. Dangers include heat stroke (with summer temperatures often over 100 degrees), dehydration, and attacks—robberies, rapes, and murders—by bandits as well as capture by border patrols.

Discarded sweatshirt and stick at State of Exception/Estado de Excepción

Another display presents many of the found objects, including: shoes, dentures, cellphones, cans, clothes, a child’s pants with embroidered flowers, toothbrushes, combs, religious icons, medicine, and a baseball cap that says “9/11 We’re Still Standing.” The wall of backpacks is the most visually powerful section of the exhibit. The hundreds of backpacks, many ragged and dirty, completely cover the wall. This section also includes excerpts of original recordings of audio interviews with migrants, also part of De León’s research. The recordings come from hidden speakers in the wall, as if the backpacks themselves are speaking. The migrants describe their crossings. “I felt like I was almost dead,” one young woman says.

Many of the migrants are escaping crushing poverty or drug cartel violence, and feel that their only viable choice is the dangerous trek to the US. In the 1990s, when the United States cracked down on immigration from Mexico by increasing border patrols and erecting walls near border towns, migrants were pushed to cross in dangerous rural areas. De León characterizes this strategy as “prevention through deterrence,” and says forcing migrants into deadly terrain that may very well kill them is a form of passive violence.

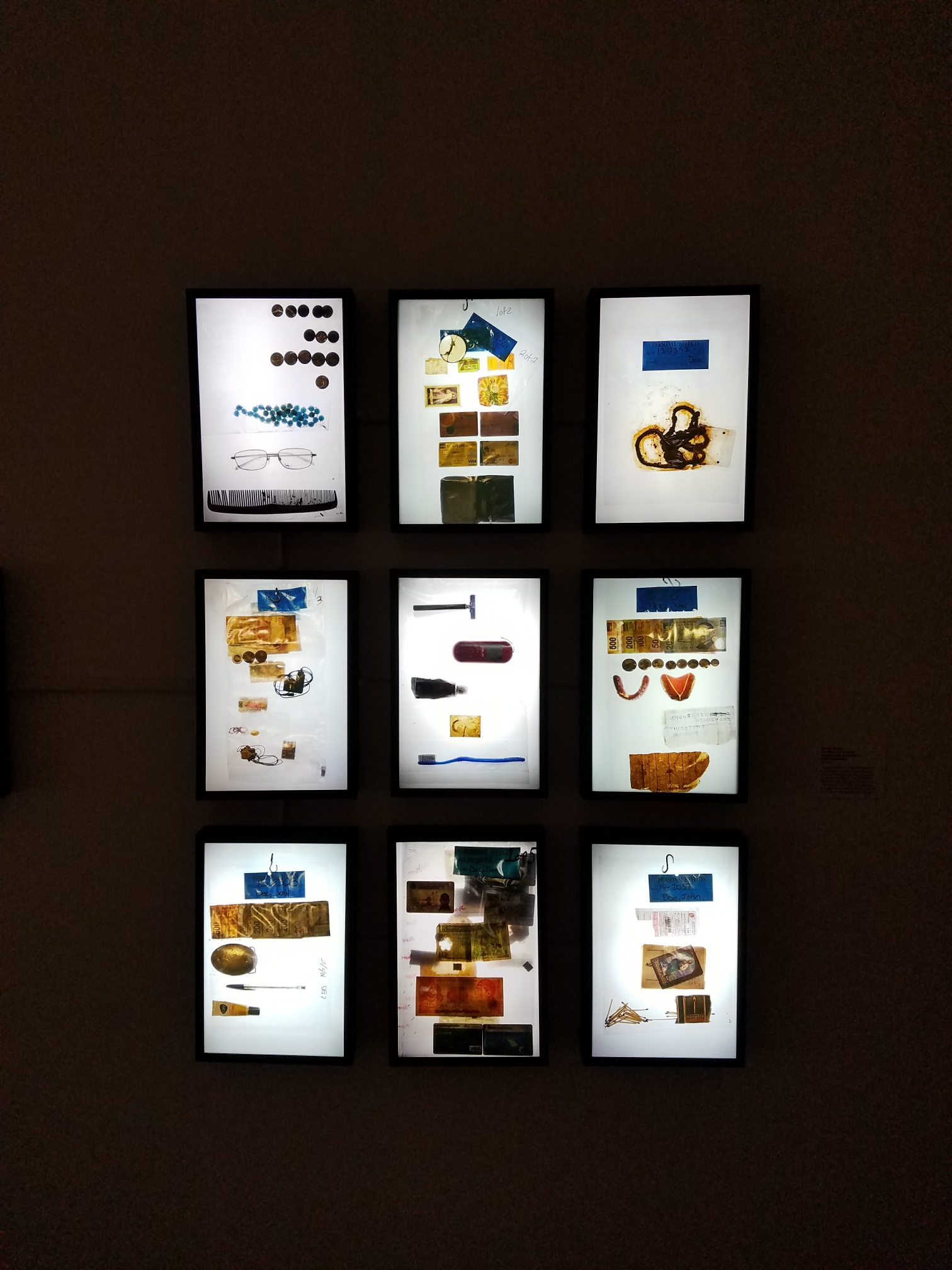

Richard Barnes / The Things They Carried / Migrant Death Artifacts 1-9

Another section of the exhibition features artifacts specifically from those who died making the crossing, many of them unidentified. These are part of an archive kept by a nonprofit group in Tucson called the Colibrí Center for Human Rights, which was formed to locate the next of kin of dead or missing migrants. When conducting research, De León and his group of students came across the body of a young Ecuadorean woman who had died attempting the crossing. The exhibit features photos of some of the students who, in the young woman's memory, later had the GPS coordinates of where she was found tattooed onto their bodies.

Artist/photographer Richard Barnes and artist/curator Amanda Krugliak created this exhibit in collaboration with De León based on the book, The Land of Open Graves: Living and Dying on the Migrant Trail. The exhibit is still evolving, constantly updated to include De León’s latest findings. The found objects are a way to look ”deeper into the migrant experience and raise questions as to what the future may hold for the thousands of people fleeing dire poverty, drug cartel violence, and political instability to the south.” The exhibit is on display at the Parsons Greenwich Village location through April 17, 2017.