One of the things I like most about living in New York and working in immigration law is my exposure to a diversity of languages and dialects. As a global capital, New York is lucky to have thriving language communities representing languages from all over the world. And yet it cannot be denied that migration plays a role in some major language shifts and language loss.

Very often, home languages do not last beyond one or two generations of Americans. Some immigrant parents refuse to teach the home languages to their children for fear that it would stunt their abilities in English or leave them with accents that could invite discrimination. Even children raised with their parents’ native language may lose it over time as they grow up and connect less and less with the home culture.

Languages Loss

Other times, language loss happens because of forced displacement, deliberate government policy, or for social or economic reasons. In an increasingly globalized world, language loss is occurring ever more rapidly, and—perhaps inevitably—New York is home to communities of speakers of some of the world’s most endangered languages. This presents a unique opportunity for linguists to do important fieldwork on many languages that have not been thoroughly studied previously—enter the Endangered Language Alliance, or ELA, which has as its mission not only the study but also the support of endangered languages. On its website, the ELA explains that “it is an ethical responsibility for those linguists working on endangered languages to contribute to their perpetuation as spoken languages if such a will exists in the community.”

I first came to learn of the ELA because of my interest in Celtic languages. Having already studied Irish, a Goidelic Celtic language, I was interested in learning a language from the other family of Celtic languages, the Brythonic—these include Cornish, Welsh, and Breton. Since I also speak French and have spent some time in France, I took an interest in Breton, which is spoken in some communities in the far west of Brittany in Northwest France. I discovered that there were Breton language classes being given at the ELA offices in Manhattan, and I thought, “Only in New York!”

Linguistic Treasures

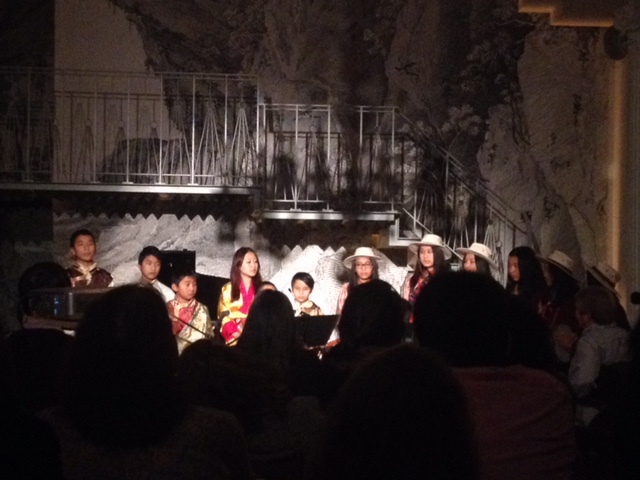

The Endangered Language Alliance event on Himalayan languages at the Bowery Poetry Club.

Through the ELA I not only enjoyed learning Breton (though I unfortunately have forgotten everything I learned!), but also came to really appreciate the work of this heroic organization. Founder and Executive Director Daniel Kaufman is a linguist with expertise in Austronesian languages and an Adjunct professor at the CUNY Graduate Center.

Mr. Kaufman has opened up the ELA tent to partner with a number of organizations, such as Breizh NY (the association of Breton language and culture in New York) and Yurumein Garifuna Cultural Retrieval (a cultural association devoted to the Garifuna language of the Caribbean) to increase awareness around language death and revitalization work.

ELA works with these and many other groups to put on cultural events in the New York area that educate New Yorkers old and new about these linguistic treasures and the fight for their survival and regeneration. I had the privilege of attending one of these events last winter at the Bowery Poetry Club in Manhattan, where the audience learned about the history and structure of several endangered Himalayan languages.

Native speakers of Mustang and Sherpa were on hand to share their language with the audience, and we were treated to traditional song and dance by a group of young children learning to carry on their parents’ traditions. I previously had the pleasure of attending a similar event focusing on Breton and Irish, and was sad to miss that year’s events on Jewish languages (Spain’s Ladino and Syrian Judeo-Arabic) and the Mobilian Trade languages (of the Gulf of Mexico coast).

When a Language Dies

The statistics on language loss and death are staggering and depressing. The fact is that most of the languages being studied and supported by the ELA will be gone before the end of this century. The ELA’s work is important in that it preserves at least some of the cultural knowledge for future generations, but once dead, languages only very rarely come back to life. When a language dies, the unique knowledge and meaning of that language in its words, modes of speaking, and grammar die as well.

The ELA’s devotion to not only recording and preserving but also supporting and regenerating endangered and threatened languages is inspiring. Their important work has been profiled in such places as CNN, the New York Times, BBC, and NPR. By taking leadership from and providing a platform for immigrant communities to celebrate their own cultures and languages, the ELA helps to enrich the New York cultural landscape.