Growing up, I never felt incredibly “American.” Though I never heard a family member speak a language other than English, and we had no relationships with relatives in the “old countries,” three of my four grandparents were first generation Americans and there was always a great deal of talk of being Swedish (on my father’s side) and Norwegian (on my mother’s). Though I am my parents’ third child and they had already been married for sixteen years by the time I was born, throughout my childhood I remember my Norwegian grandfather continuously teasing my father, his son-in-law, for being Swedish. We would sometimes come home from visits to the Tjemsland house with Swedish pancake mix because my Grandpa Arnold insisted he could not keep anything in his home that bore that name. It was never entirely clear how serious this “joke” was.

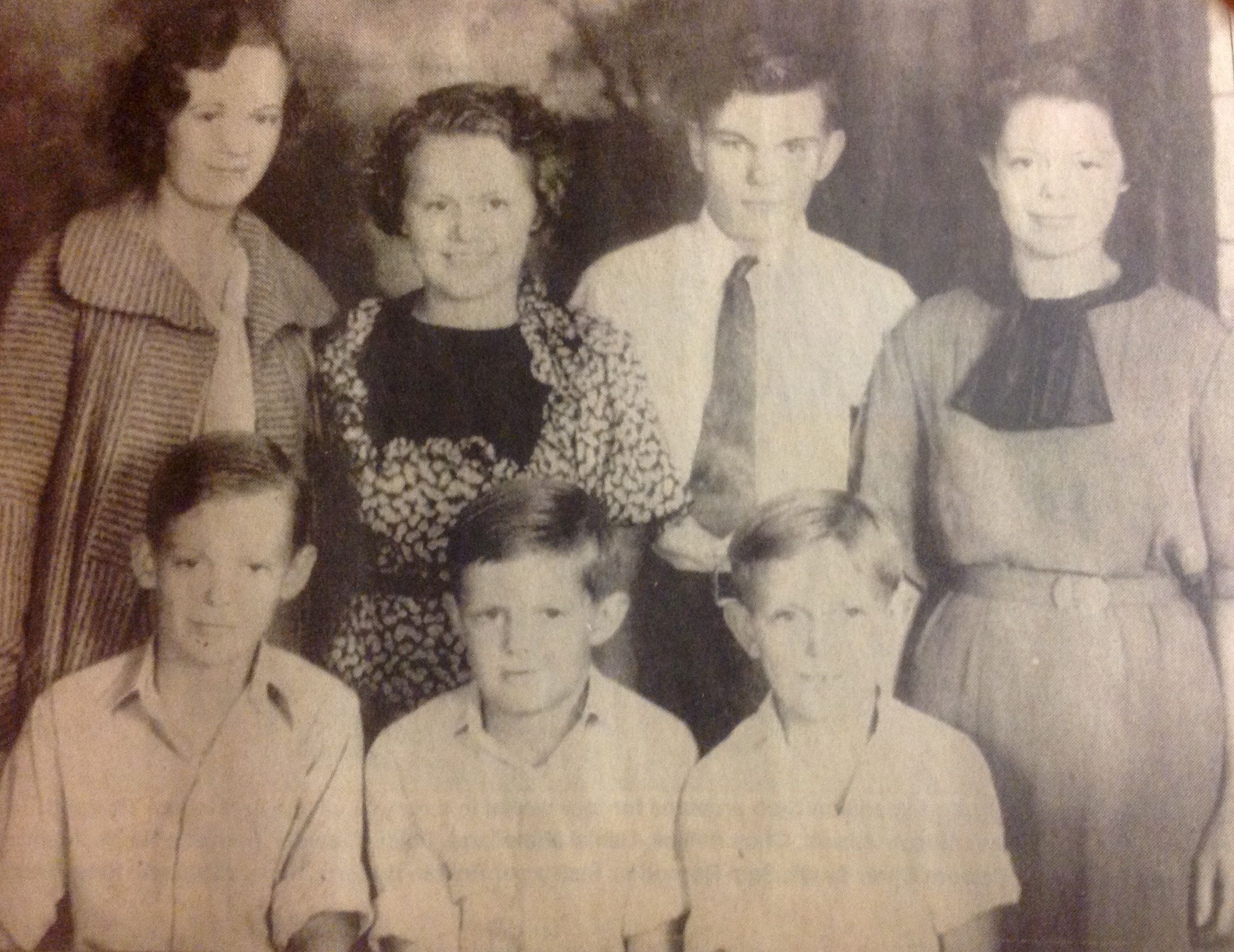

My mother’s father, Arnold Tjemsland, was the youngest of seven children born to Norwegian immigrants Ole and Elenora Tjemsland, who each traveled to the United States individually as teenagers during the first decade of the 1900s. At the age of fifteen, Ole traveled from northern Norway to live with his sister’s family in North Dakota. Shortly thereafter, seventeen-year-old Elenora left southern Norway to stay with relatives in Minnesota. A shortage of work in Norway led many young people to leave for America at the time, where a growing economy meant there was a need for labor.

At that time in the United States, the 1862 Homestead Act was still in effect, an attempt by the US government to populate the West by offering 160 acres of free land to any person who could work and improve that land within five years. One needed only to be twenty-one years of age or the head of a household to claim the land, which opened up enormous opportunity for a wide swath of people to begin their lives in earnest, including former slaves, single women, and newly arrived immigrants. Both Ole and Elenora took advantage of this offering, each individually homesteading in Montana, which was where they eventually met, through relatives. Their first three children were born in Montana, before the young family moved to Washington state, following one of Ole’s sisters, in 1919. Norwegian was spoken at home until my grandfather’s three oldest siblings enrolled in school in Washington, at which point a visit from a teacher encouraged the family to begin speaking only English.

My mother’s mother, Alexia Tjemsland (née Richmond), was the daughter of Scottish immigrants who also met in the United States after leaving Scotland on their own devices. My mother was particularly close to her grandmother, Magdalena Richmond (née Norrie), and my middle name is Norrie, after her. As a funny side note: My mother and I traveled to Scotland when I was studying abroad in London in college, and visited my great-grandmother’s hometown of Broughty Ferry (a suburb of Dundee). While there, we went into a shop where you can look up your family’s name to find your crest or tartan. When we searched for “Norrie” in the database, one word came up: “Norwegian.” So while my mother always thought she was half Norwegian and half Scottish, it seems a good deal of the Scottish is probably Norwegian as well. (I can’t help but wonder about that immigration story.)

My father’s father, Albert Roblan, was also a youngest child, born to Swedish immigrants Axel and Ingaborg Roblan. Like Ole and Elenora, Axel and Ingaborg arrived in the United States separately and met and married in their new country. “Roblan” began as the Swedish name “Rodblüm.” Technically from Finland, Axel Rodblüm was virtually born an immigrant, as part of a large historically-Swedish community in the Finnish city of Turku, known to Swedes as Åbo. The oldest city in Finland, founded at the end of the 13th century, Turku is still home to the only Swedish-language university in Finland, and more than five percent of the city’s population still speaks Swedish as a first language.

Axel Roblan (my great-grandfather).

Axel was put onboard an international fishing boat at the age of twelve, as a means of financially supporting his family, who were helped by the wages he sent home. This arrangement, however, was clearly not what the young man had in mind for his life, and when the vessel was docked briefly in Washington state when he was sixteen or seventeen, he jumped ship, and stayed in Aberdeen for good. No one knows whether the name change from “Rodblüm” to “Roblan” was deliberate or due to someone attempting to phonetically spell it out, but it stuck, and because it’s a made up name, there is roughly a 99.9% chance that any Roblan you find in a Google search is related to me. (So far, the only Roblan I’ve found who isn’t a relation is Cuban Fidel Castro impersonator Armando Roblán—he made up his last name, too.)

Once in Aberdeen, Axel met Ingaborg Lundgren, another Swedish immigrant who had moved to Aberdeen with her family as a young woman—the only one of my immigrant great-grandparents who did not make their voyage to America alone.

The only one of my grandparents whose parents were born in America was my father’s mother, Carrie Roblan (née Crawford). My grandfather spoke openly about the fact that part of his initial attraction to Carrie was her “American-ness.” He was a quiet, contemplative Swede. She was brash, assertive, and loud. They met in the middle of World War II while he was a soldier and she was working in a factory. She could have been a model for the Rosie the Riveter poster, and their Victory Day kissing photo definitely rivals the iconic Times Square sailor one.

My grandparents, Albert and Carrie Roblan, at the end of World War II.

I always knew that my Grandma Carrie’s family had moved to Washington from Illinois, but we didn’t know much beyond that. When I moved to Brooklyn five years ago, I felt completely alien to the East Coast, with about two friends in New York, and (as far as I knew) absolutely no family ties. Around the same time, though, my older sister was becoming more and more interested in genealogical research, and happened upon a family tree online that a distant cousin had assembled for my grandmother’s family. She sent it to me, and, together over the phone, we searched back through every connection in that tree, finding birth, death, and marriage records that corroborated and evidenced all of the relationships.

The end result showed that we were the direct descendants of Sarah Rapelje, the first woman of European descent born in New Netherland in 1625—the settlement that would become New York. Her daughter, Rebecca Bergen, our twelfth great-grandmother, was born in New Amsterdam (modern day Brooklyn), and would go on to marry Aert Middagh, one of the original petitioners who formed the village of Brooklyn. There is still a street in Brooklyn Heights baring their family name.

Ultimately, what I find fascinating about the convergence of all these family trees is the wide variation in immigration experience that ends up becoming an incredibly American mixture. It involves legal homesteaders, illegal immigration, the complicated history of European colonization, and many independent-spirited fearless young people seeking to create entirely new lives in a brand new place.