My father, Walter Blank, is in the front row, second from the left. 3rd US Infantry Regiment.

I’m an American Jew, the kind that bleeds first for the Constitution, the Knicks, rock ‘n’ roll, and Levi’s blue jeans, and second, for “the old country” as my father used to call it. I was born in Washington, D.C. and grew up in Northern Virginia and suburban Maryland, but I’ve always felt the breath of my ancestry on my neck. My immigration experience is second-hand, one borrowed from my parents and their parents before them and so on and so forth. From Exodus to exile to Ellis Island—that is my family’s Jewish experience.

America has been a refuge to Jews since the US Constitution was enacted in 1789. Seeking to reassure and guarantee the religious and civic liberties of Jews in the newly formed US in 1790, George Washington wrote in the Letter to the Hebrew Congregation at Newport that “the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens in giving it on all occasions their effectual support.” In America, he wrote, “every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and fig tree and there shall be none to make him afraid.” America opened its arms to people of all faiths to live here freely, participate in its civic institutions, and practice their religion freely. Such freedom and inclusion was not afforded to Jews in Europe. These freedoms would be the beacon drawing Jewish immigration to the US from the nation’s infancy through to the postwar era.

My Grandpa Coleman and Grandma Ruth.

My maternal family immigrated to the US seeking refuge from pogroms in Eastern Europe. They came from The Pale of the Settlement, the western regions of the Russian Empire where Jews were allowed to live, which included Lithuania, Belarus, Poland, Latvia, and Ukraine. My mother’s side of the family immigrated to the US in the 1880s and 1890s. The Czar of Russia forced them to leave their village in Lithuania. They came to the US at a time of massive Jewish influx, and were fortunate to enter the US before the Immigration Act of 1924, which sought to restrict immigration of people from Southern and Eastern Europe. My grandmother Ruth was born in Buhl, Minnesota in 1919. She used to babysit a young Robert Zimmerman, better known as Bob Dylan. My mother was born in Detroit in 1950 and raised on 8 Mile Road, the same 8 Mile Road that Eminem came from.

Grandma Rose and Grandma Jack. (Picture is unfortunately distorted because of age.)

My paternal grandfather Jacob “Jack” Blank left Poland in the early 1930s as Hitler and the Nazis were coming to power. He came to New York through Ellis Island and eventually helped his parents and siblings come to America “before things got worse in Europe,” as the story goes. My grandmother’s paternal grandfather was a Grand Rabbi in his town in Poland. His children and four grandchildren, including my grandmother Rose, left Poland in the mid-1930s, also entering the US through Ellis Island on tourist visas. She lost twenty family members in the Holocaust. I was always told getting into this country was extremely difficult for Jews at that time. My grandmother Rose started working at a sewing factory. She was as beautiful as any 1930s movie star and she eventually became a fashion model. She joined both a union and the Communist Party, which she stayed active with until her death. She also took my then-young father to stand outside the prison in protest when Julian and Ethel Rosenberg were executed for treason and passing nuclear secrets to the Soviets.

Jack worked as a teacher, eventually becoming an Honorary Professor of Judaica at the Jewish Theological Seminary at Columbia University. He devoted his life to saving the Yiddish language and gave lectures across the country. He also taught Yiddish as part of the Workman’s Circle at New York City Public Schools in Canarsie, Brooklyn. He was also a regular contributor to The Forward, an influential socialist Yiddish-language daily newspaper. Jack and Rose met while working with the Yiddish Theater Company and were mutual friends with well-known actors of the Yiddish Theater, including Molly Picon, who was Yenta the Matchmaker in the original Broadway production of Fiddler on the Roof.

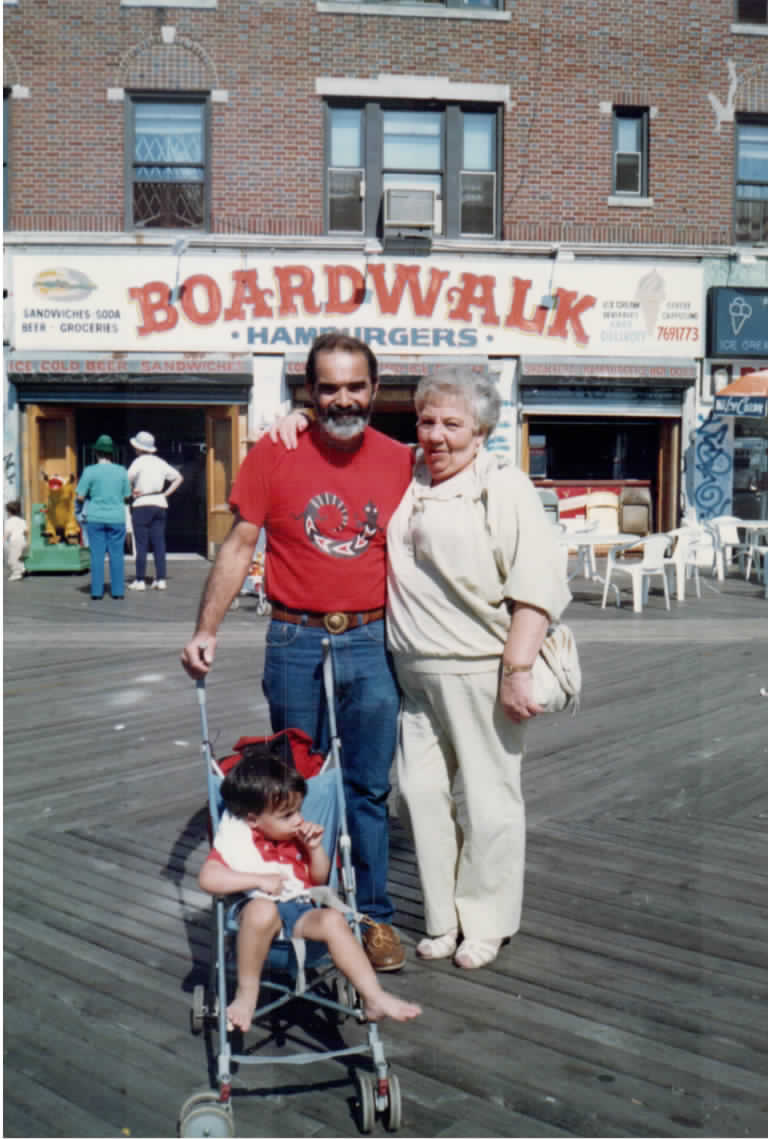

With my father and Grandma Dina at Coney Island.

My father Walter was born in Brownsville, Brooklyn in 1935. He grew up in tenement housing and his first language was Yiddish. My grandmother Rose passed away before I was born and Jack passed away when I was one year old. Dina, Jack’s fourth wife, was like a grandmother to me. Dina survived Auschwitz. She lived in a refugee camp after the war, where she married another refugee, and had two children. Eventually, they too came to the US, where after her husband died, she met my grandfather.

My dad always loved being an American, playing stickball in the street, hanging out on stoops, going to see the Brooklyn Dodgers, and getting into trouble as young boys in Brooklyn do. After he graduated from Boys High in Brooklyn he enlisted in the army and served in the 3rd United States Infantry Regiment, the Old Guard. This was after the Korean Armistice Agreement and before the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. He always said he was proud to serve in the army. Immigrants showed allegiance to their new country by sending their sons to war. “Immigration is not an easy thing,” he would often say. “No one wants to leave home. If they could stay with their family and not make the sacrifices required to immigrate to a new land, they would.” He was the last direct link to the family’s immigration story and a world, a New York, that no longer exists.

The essence of the Jewish experience is that of a stranger in a foreign land. Here, countless generations have wrestled with their identities and assimilation. I have always felt privileged to grow up in America, receive a first class education, and experience many wonderful things. It’s quite possible that I may not be here had my family not survived oppression and sacrificed so much to immigrate here, and I take pride in my work at the firm every day knowing that I help ease people’s transition to this great country.