The stories of people’s cultural backgrounds, how they came to America, and the cultural traditions they brought with them are fascinating to me. That’s part of why I became an immigration attorney and why my own family’s immigration story is one that I have thoroughly explored.

Theodore was famous for the way he could casually lean on columns.

My mother’s side of the family comes from England through a line that can be traced back to the earliest American settlers, including a Francis Drake (who our family thinks may be a descendent of the Sir Francis Drake but have yet to confirm) who settled in the colony of New Hampshire. An alleged religious dispute with the Puritans caused him to move his family further south. With multiple generations of my family living in Connecticut, it’s ironic that I was already living in Brooklyn, NY when my mother and aunt decided to start a genealogy research project and discovered that my great-great-great-great-grandfather Theodore Drake spent most of his life in Brooklyn, NY and is buried in Greenwood Cemetery—only blocks from where I live now. Theodore Drake turned out to be an interesting character. If I were on the show Finding Your Roots (if it ever comes back on the air—thanks Ben Affleck and Henry Louis Gates Jr.!) he would surely be the character they focus on (apart from Sir Francis Drake).

Theodore's tombstone in Greenwood Cemetery.

Theodore fought in the Civil War and afterwards served as an honor guard when President Lincoln’s funeral procession passed through New York City. He spent three years on the USS Macedonia, on the squadron comprising the famous Commodore Perry and was part of the first expedition to Japan in 1853, when parts of that country were opened to the US. (Previous to this journey, Japan had isolated the country from any foreign visits with the exception of one Dutch ship per year.) Commodore Perry and Theodore were stationed at the Brooklyn Navy Yards. A few years ago, my mother, my aunt, and I searched for Theodore’s grave among the thousands buried at Brooklyn’s Greenwood Cemetery, and found it—still in relatively good condition for its age.

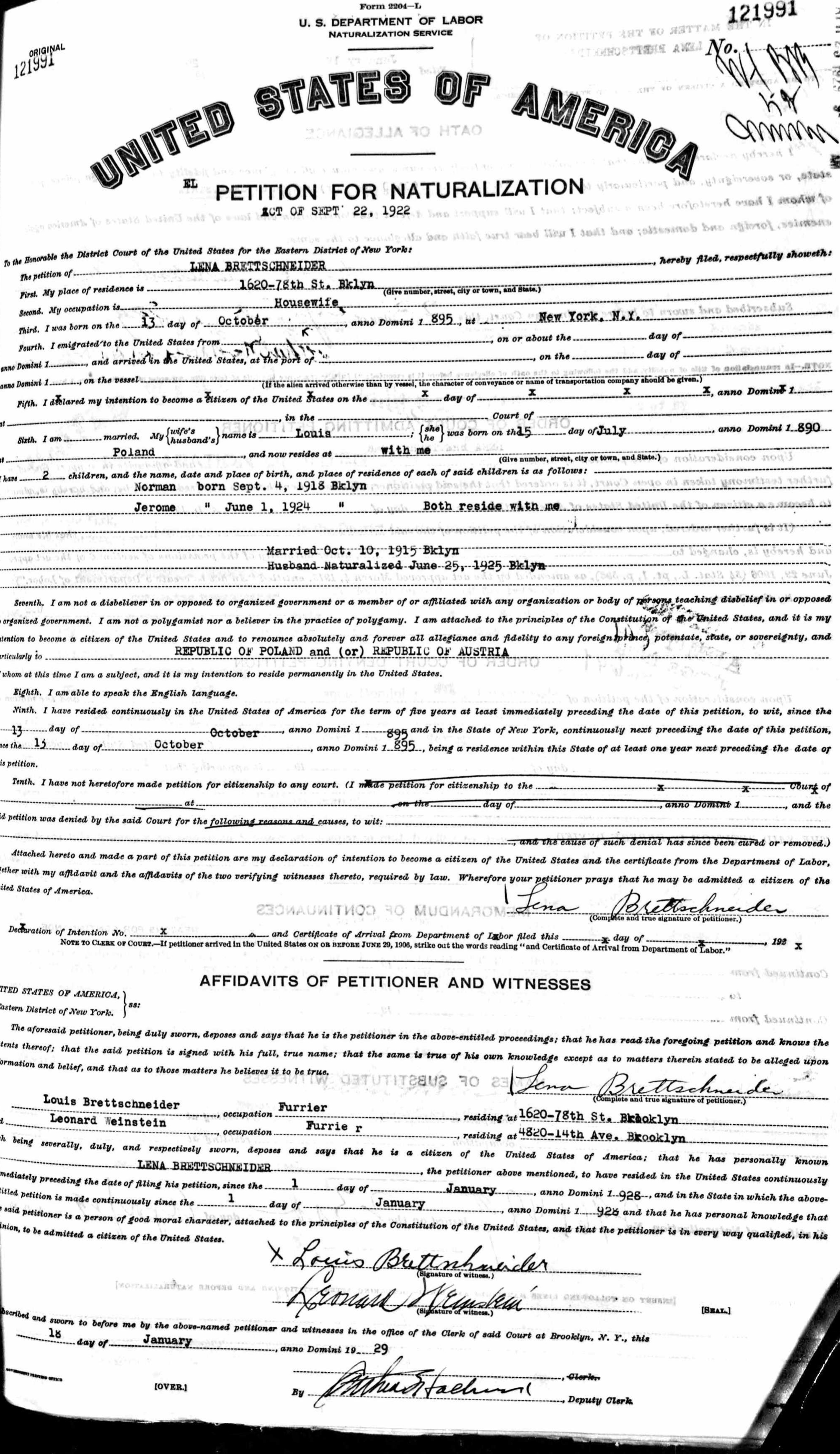

My father’s side of the family also has modern roots in Connecticut and a Brooklyn connection. Through extensive research, we were able to locate the naturalization records of my great-grandparents. (Naturalization is the process of gaining US citizenship for people born outside the US.) Not only did the certificates reveal their address in Brooklyn, but I also discovered something deeply puzzling. My great-grandmother, who was born in New York, NY, had entered a petition to naturalize. The fourteenth amendment of the US Constitution was passed in 1868 giving everyone born in the United States citizenship. Since she was born in 1895, why would she be required to apply for citizenship? As an immigration attorney this made no sense to me so I did some research to understand why.

My great-grandmother Lena, who was born in the US, married my great-grandfather Louis Brettschneider, a Polish citizen, in 1915. At that time, upon marriage, wives took on the legal identity, and, it turns out, citizenship of their husbands. Commonly people know this in relation to property rights but lesser known (at least to me) was that wives also lost their independent citizenship. Foreign women who married US citizens automatically gained US citizenship but that also meant that US citizen women who married foreigners automatically lost their US citizenship and took on the citizenship of their husband.

My great-grandmother's naturalization certificate.

That’s why on my great-grandmother’s naturalization certificate she had to renounce her loyalty to Austria and Poland even though (as far as I know) she never stepped foot in those countries. It was my great-grandfather who was born in a region in Eastern Europe once part of Austria and later Poland. He eventually naturalized in 1925, likely based on his many years of living in the US. At that time the immigration laws were undergoing a lot of change that affected women’s citizenship rights. In 1922 Congress passed The Cable Act, which finally granted married women independent citizenship rights. What this means is that by the time Louis naturalized in 1925, Lena didn’t automatically assume her husband’s new citizenship; thanks to the Cable Act she maintained her independent citizenship, and was still considered a citizen of Austria/Poland, which citizenship she had acquired when she married Louis who had been an Austrian and Polish citizen (before the Cable Act). Thus, she needed to file a naturalization application in order to regain her US citizenship.

I wonder what advice I could have given to my great-grandmother Lena had she come into my office in 1928 wanting to regain her lost citizenship. I wonder what she would have thought about having to petition to be a citizen in her birth country, and I wish I could have helped her navigate the rapidly changing immigration laws of that era. I love that the study of genealogy and making connections to those who came before me can make the world seem a bit smaller. I also think it’s ironic that a Polish Jew from Eastern Europe and a descendant of Sir Francis Drake from England can follow similar paths from foreign lands to Brooklyn, NY, where after growing up in Connecticut I also “landed.”